The line between creative inspiration and infringement can be thin, dotted, or invisible at times. This was one of the lessons that Adidas had to learn this month when it lost its $8 million lawsuit against American fashion label Thom Browne over the use of parallel stripes in their designs. The German sportswear giant, who filed the lawsuit in 2021 saying that Thom Browne’s use of the stripes infringed on their trademark logo, believed that the use of the striped design was “confusingly similar” to the one presented in their logo. In 2020, global fashion brand Zara was sued by a smaller luxury label, Amiri, for copying a design of jeans without permission to use the design that included pleated leather panelling and zippers around the knee; after which the two brands decided to settle. And, more recently, French luxury brand Hermes has sued NFT artist Mason Rothschild for creating and selling NFT digital images of their famous Birkin bag, saying that the name of his work, entitled “MetaBirkin”, appropriated the Birkin trademark.

At the crux of these lawsuits, along with many others, is a conundrum of creative expression, trade infringement, artistic licence and consumer confusion that affects D2C brands both small and large. As the fashion category within retail is so often pushed forward by something as ambiguous as creative expression, is there a defined lane that brands must stay inside of to avoid causing a fashion collision? Are fashion and beauty brands blurring into a homogenous cauldron of shared creativity? Do fast-fashion brands like SHEIN, Revolve, H&M and Zara get away with copycat behaviour because of their overall size and influence in e-commerce?

Copyright and intellectual property laws may favour fast-fashion giants

“Designers could not claim protection for any and all sweaters simply because they happen to make sweaters. But they can copyright the creative aspects of their work that make it different from the norm, such as a unique pattern,” says lawyer and Editor-in-Chief of The Fashion Law Julie Zerbo. “The reality is, in most cases, it's perfectly legal to knock off a dress design,” says Zerbo, which is why Amiri’s case against Zara resulted in being settled out of court as Zara made the case that the skinny jeans were “generic, ornamental and not distinctive” enough for Amiri to act on protectable trade dress rights, according to their legal representatives.

In a similar instance, Nigerian designer Elyon Adebe found a replica of one of her crochet sweaters on SHEIN, the Chinese fashion brand that is the most-installed shopping app in the US; which seems to have copied the design and the colour scheme. The handmade garment was priced at $330 while the sweater on the e-commerce giant was priced at $17, catering to the Generation Z (aged 11 - 26) market that has largely contributed to SHEIN’s success. The copied sweater was removed from SHEIN’s website after Adebe posted about it on social media.

The fact that many fast fashion behemoths are able to infringe, borrow or take inspiration from smaller D2C brands without much financial or social recourse leans toward a point made by Eleanor Rockett, author of the academic paper “Trashion: An Analysis of Intellectual Property Protection for the Fast Fashion Industry” published for the University of Plymouth, who said fashion is an industry “with copying at its heart” but further thickens the grey area when saying, “Intellectual property protection must strike the appropriate balance between inspiring innovation and restricting imitation.” She also references a theory that suggests copying spurs on innovation instead of stifling it, by saying that the more a trend or design goes viral, the faster it becomes irrelevant, in turn making for ripe conditions for more design innovation.

European copyright law offers wider protections than in the US

Rockett states how lax the intellectual property laws are in the US, which is supported by Zerbo’s thoughts above, and that the openness of them actually encourages copying and hastening the fashion cycle so that new designs can be made. In Europe, however, the requirements needed to be protected by copyright law offer far more coverage in the sense that there are only two requirements to meet:

- The design’s originality. It must be proven it is the creator’s own intellectual property

- The design must have the ability to be expressed in an exact and objective manner by an individual

American law only offers protection if there are distinguishable features on the garment while European copyright law gives brands and designers wider protection. For example, in 1994, French luxury label Yves Saint Laurent (YSL) sued Ralph Lauren for copyright infringement. YSL’s dress was black, full-length, made of silk, had gold buttons, no pockets and a narrow lapel. The Ralph Lauren dress was black, full-length, made of wool, had black buttons, included pockets, and a wide lapel. YSL still won despite the dresses in question having unique characteristics, and took home €323,000.

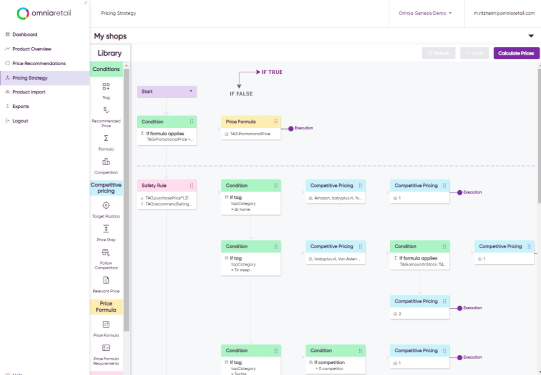

Find out more about how Omnia can help brands with price monitoring.

Are fashion and beauty brands blurring into a homogenous cauldron of shared originality?

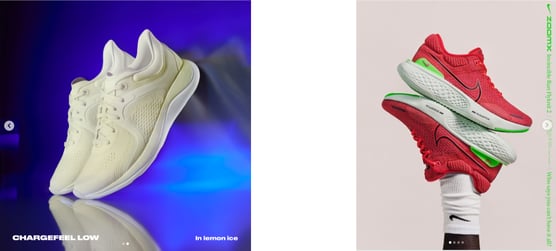

Shared originality - something that can’t quite technically exist but is tending to spread within fashion and beauty retail. Just this week, Nike sued Lululemon for patent infringement, accusing Lululemon of using some of Nike’s flyknit technology in their lifestyle sneakers. Although both brands produce sportswear and lifestyle shoes and clothing, their markets, branding, identity, ethos and marketing strategies are completely different; however, something that used to be a uniquely Nike product is now - kind of - Lululemons too. In addition, prior to this, Lululemon did not include any shoes as a part of their offering, making the fly knit look-alike their first venture into offering sneakers. In the past, Adidas has been accused of using fly knit technology in their Primeknit shoes too, adding fuel to the fire that proprietary designs and formulas that are used, borrowed or outright stolen make for a market that lacks individuality.

While the shoes may not look similar, it is the fly knit technology patented by Nike in 2013 that

Lululemonhas allegedly infringed upon, which is a knitted textile used in Nike's running shoes.

Credit: @lululemon Instagram Credit: @Nikerunning Instagram

Eventually, will everything look the same to consumers? Because branded items are losing their distinctiveness, consumers may opt for an item that looks similar to one they truly want, but is cheaper, thus increasing the competition within pricing. Brands are now not only competing on a product level, but on a pricing level because said products are becoming homogenised.

The same can be said within beauty which has seen an explosion in market saturation in the last five years. If Chanel and MAC release liquid concealers within just a few months of one another that both offer pore-blurring technology, the product is no longer bespoke and the consumer can begin to choose a winning product on a price level, pushing forward the snowball effect that stepping on another brand’s proprietary technology only leads to a price war in the market.

Although brand individuality is blurring, consumers can enjoy the unintended benefits

When it comes to pricing, it works in the consumer’s favour when brands with similar products compete; keeping prices steady for shoppers. If there was no competition in pricing, there would only be monopolies; stifling opportunity and competition for new, smaller brands. When Andrea Saks from “The Devil Wears Prada” was on the receiving end of a scathing monologue from Miranda Priestley, played by Meryl Streep, for making a snarky comment about high-end fashion, she learnt that the “lumpy blue sweater” she was wearing wasn’t an exemption from the fashion industry, but very much a cog in the machine of it. Priestley's point was that fashion is not only cyclical, but shared, easily influenced and even more influential. Fashion is an industry full of brands and trends that either intentionally or unintentionally step on each other’s toes when it comes to designs, formulas or technology; all in the name of attracting and holding consumer demand. This is not to say that trademarks are up for grabs, and brands have the right to protect what they have built. Ultimately, the consumer must decide how they go about navigating the flock of brands that are all starting to look like doves and this is at times where dynamic pricing for D2C brands plays the biggest role for the consumer.

.png?height=766&name=ORA%20Visuals%2020252026%20(11).png)